Just as William and Elizabeth (Bunting) Sauls begin their lives together as a married couple in October 1849, they are enumerated in three different censuses a year later, providing a clear picture of their household. The October 31, 1850, Agricultural Census Schedule is the most revealing and indicates that William is primarily a hog farmer on land he doesn’t own or that has no cash value. His livestock consists of 2 horses, 3 milch cows, and 20 swine, valued at $150. The produce includes 500 bushels of Indian corn, 10 bushels of oats, 15 bushels of sweet potatoes, and 75 pounds of butter, all valued at $31. Additionally, there is a value of $45 for slaughtered animals. The 1850 US Schedules of “Free Inhabitants” and “Slave Inhabitants,” both dated November 14, 1850, show that William and Elizabeth are the only free individuals, accompanied by their five enslaved individuals. Though not named, the enslaved are identified as three black males, aged 30, 20, and 5 years old, and two females, one mulatto aged 20 and one black aged 3. William and Elizabeth are identified by name, age, and gender. William is a farmer and has a real estate value of $1800. Since the agricultural schedule states the land had no value, we know this $1800 reflects the value of the enslaved individuals. These individuals are as important to this household as the free ones, as they will do the brunt of the work to help the household prosper in the future.

William and Elizabeth remained in Hardeman County, Tennessee, until around 1855 before they began making their way west. They had two daughters before leaving Tennessee; the first of whom died there and was buried in the Bunting Cemetery. Find a Grave documents her existence as Mary Jane Sauls, who died in 1853 at 15 months and 27 days old, daughter of W. M. and E. C. Sauls. The approximated birth dates of their following two children, listed on the 1860 census indicate that the family left Tennessee after 1854 and before 1857. The second child, a daughter referred to only as C. C. Sauls, on this census record, was 6 years old and born in Tennessee. The third child, a son listed as W. B., was 3 years old at the time and was born in Arkansas. Neither of these two children are found in the 1870 census, indicating they likely died in Arkansas.

| Year | Acreage | Slaves | Horses | Mules | Cows | Total Value |

| 1855 | 160/$480 | $480 | ||||

| 1856 | 200/ $600 | 4/$3400 | 1/$60 | 3/$225 | 1/$10 | $4295 |

| 1857 | 200/ $600 | 4/$3400 | 1/$60 | 3/$225 | 1/$10 | $4295 |

| 1858 | 400/ $1200 | 3/$1800 | 2/$150 | $3150 | ||

| 1860 | 240/$720 | 5/$5000 | 1/$40 | 3/$360 | 8/$80 | $6200 |

| 1863 Warren Twp | 240/$720 | 5/$3000 | 1/$50 | 2/$200 | 4/$60 | $4030 |

| 1865 Clay Twp | 1 Lot/ $100 | 2/$20 | $140 |

These tax records do not specify which crops William farmed. Although later tax records list values for cotton and corn production, the mainstays of the South. This area of Arkansas was very difficult to navigate since there was no large river in Columbia County, and the bayous and deeply cut creeks made travel even more challenging. Additionally, the wetter climate of this region worsened the difficulties in traveling the roads, which delayed the construction of railroads until the 1880s

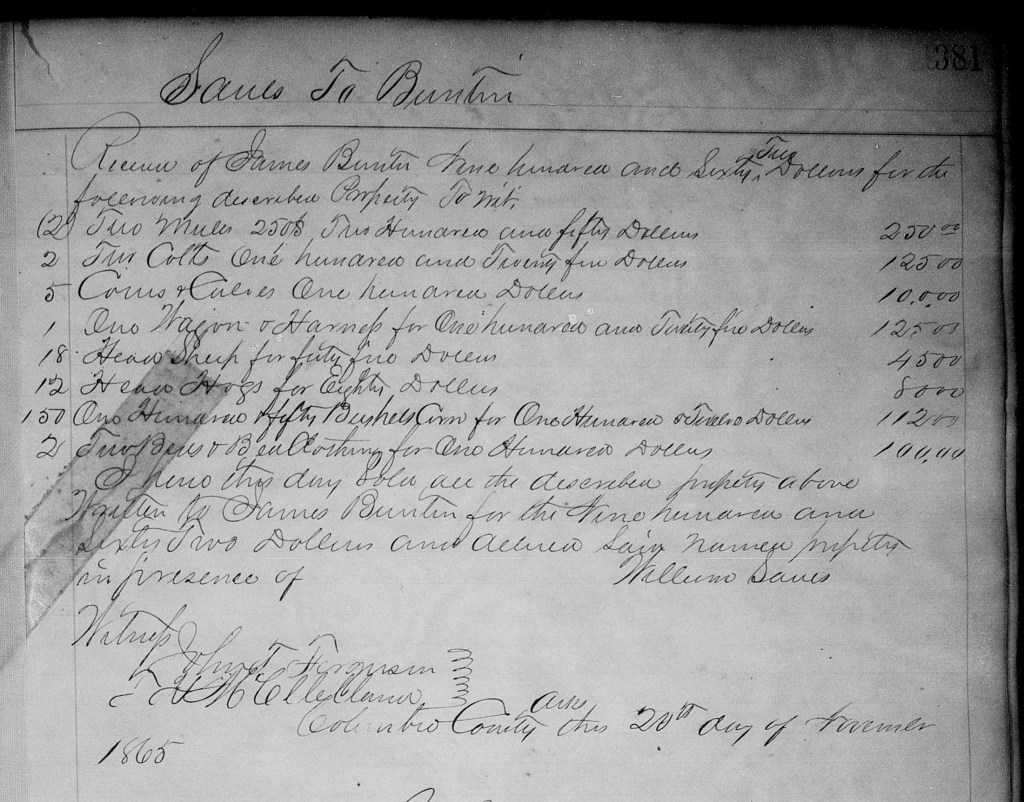

By the time the Civil War began, the family farm was thriving and the family was growing. Another daughter, Virginia S., was born on September 21, 1859; a son, Samuel, was born around 1862; and then another daughter, Julia L., arrived in 1864, when they were definitely feeling the decline. The Civil War was not favoring the South, and William began to sell off his holdings in Arkansas. William sold 160 acres of land, the SE quarter of Section 30, T16S R22W, to T. H. McClellan on January 11, 1864. On November 22, 1865, a sale of personal property to Elizabeth’s brother, James Bunting, signaled a bigger statement about their departure from Arkansas.

Was this sale of goods mainly to raise cash, or was it perhaps an investment for James to take back to Tennessee to sell more profitably in a better market? Or, quite simply, was it just a liquidation? It is known that James Bunting will also relocate to the same area of Texas where William and Elizabeth eventually settle. On the same day that the personal property is sold, William and Elizabeth sell 200 acres to C. A. Griffin for $800. Early in February 1866, a deed for a final piece of property, 160 acres (the SE quarter of Section 20), was conveyed to William R. Queen for $1100. The last record of their presence in Arkansas is the birth of their son, Joseph Henry, on October 8, 1867—the last child born in Arkansas who will carry on the Sauls’ name in connection with Lula Bell Stickney.

The birth of their daughter, Texanna, in 1869, marks their presence in Texas, as indicated by the 1870 census, which records the family living in the western district of Burleson County. William is again listed as a farmer with no real property value, owning only $115 in personal property. This census uniquely notes Elizabeth’s actual birthplace as North Carolina; all others incorrectly list her as born in Tennessee. A decade later, William and Elizabeth are enumerated in Bell County with six children: Samuel, age 20; Ella, 14; Joseph, 12; Texana, 11; Owen, 7; and Euginia L., 5. According to Bell County tax records, the family had left Burleson County by 1872, showing William Sauls established on 110 acres in Bell County. Two years later, William is recorded on a different tract of land containing 150 acres and remains on this property at least until 1883.

During these years, Bell County assessed tax values on land, wagons, and livestock, but not on farm produce. Wheat and corn were the main crops grown in this part of Texas, though cotton was also being introduced at that time. Fortunately, much more information about what this family relied on can be found in the 1880 U.S. Non-Population Census for Bell County, Texas. Taken on June 7, 1880, it details William’s agricultural activities as the owner of 80 acres of tilled land, 13 acres of woodland, and 58 acres of unimproved land. The value of this land, including fences and buildings, was $2,000. Farm tools and machinery were valued at $51, and livestock at $250. The cost of building and repairs in 1879 was $75. The total wages paid for farm labor during 1979 was $100. The estimated value of all farm products (sold, consumed, or on hand for 1979) was $1,000. As of June 1, 1880, the inventory included 2 mules, 3 milch cows, and 5 other cattle: 2 calves born, 8 sold alive, and 2 died or were not recovered. 200 pounds of butter were produced. There was no sheep production. As of June 1, 1880, there were 7 swine and 30 poultry. No eggs or rice production was reported. Crops produced in 1779 included: 18 acres of Indian corn yielding 150 bushels, 2 acres of oats producing 80 bushels, 17 acres of wheat yielding 155 bushels, 20 acres of cotton producing 12 bales, and finally, 125 pounds of honey harvested.

Beginning in 1888, William Sauls moved west into the neighboring county of Coryell, where tax records indicate he was located on 106 acres and provide only limited details of assessed values for the property, wagons, horses, cows, and miscellaneous items. The total values began in 1888 at $1140, after which a slight economic depression leading into the 1890s caused values to decrease to a low of $950 in 1890, but then rose again to $1080 in 1893. There are no further U.S. Census agricultural schedules available from this period to provide more detailed accounting information. The most intriguing information about this land in Coryell County is that it was part of an original grant to James Robinett, adjacent to land (originally granted to Madison Leedy), parts of which were owned by James Franklin Stickney in 1888. This is how the two children, Joseph Henry Sauls and Lula Bell Stickney, became acquainted as neighbors and would later marry, generating this branch of the Sauls/Stickney family tree.

Part 4, “The Stickney / Sauls Family – Joseph Henry and Lula Bell (Stickney) Sauls” is coming soon.