William and Elizabeth (Bunting) Sauls were united in holy matrimony on October 22, 1849, in Hardeman County, Tennessee, by Samuel Lambert, as noted on the back of the marriage license found in the Tennessee State Library and Archives, which are available on Ancestry.com. William would have presented this license to Lambert to marry Elizabeth, and Lambert would later file it with the Hardeman County clerk. William acquired this license on October 18, 1849, as an accompanying bond was needed (also viewable on Ancestry) and was signed by William and his surety, John H. Raines. They were responsible for the legality of the marriage, ensuring that neither the bride nor the groom was already married to others, that they were of legal age, and that both lived in Hardeman County. If any conditions existed that prevented or negated the marriage, Raines would be responsible for paying any resulting damages. It can be difficult to determine how old William and Elizabeth were when they married, since during this time period, birth records were not officially kept and were not considered as important as marriage, which had legal ramifications. For Elizabeth, these unofficial records that noted her age in a given year varied significantly. It was not suspected that William and Elizabeth were underage since the legal marriage age in Tennessee was generally considered to be 14 years for males and 12 years for females, based on the English common law that was largely adopted in the United States at the time, allowing for marriage at these younger ages with parental consent. Indications were that they were on the younger side of age for brides and grooms, even by 1850 norms, not to mention modern ones that instigate this investigation.

In examining the unofficial records that indicate an age or birth year, William’s information was quite consistent, confirming his age as eighteen; however, Elizabeth’s records were inconsistent, suggesting her birth year could range from 1833 to 1845. The chart below illustrates the discrepancy between census records.

| Census Date | Name | Age | Calculated Birth Year | Birth Place |

| 14 Nov 1850 | Elizabeth Sauls | 17 | 1833 | TN |

| 14 Sep 1860 | E. C. Sauls | 24 | 1836 | TN |

| 23 Aug 1870 | Sauls, Elizabeth C. | 33 | 1837 | NC |

| 6 Jun 1880 | Sauls, Elizabeth C. | 35 | 1845 | TN |

| 9 Jun 1900 | Sauls, Elizabeth C. | Apr 1835, age 65 | 1835 | TN |

| 25 Apr 1910 | Sauls, Elizabeth | 75 | 1835 | TN |

Census information is not an official record, and its accuracy greatly depends on who provides the information. Dates on grave markers are often used to indicate the finite times an individual was present on Earth, but they are not necessarily accurate. The stone marking William and Elizabeth’s final resting place in Jonesboro Cemetery, just outside Jonesboro, Texas, was likely placed long after each had died. William’s and Elizabeth’s specific dates of death are accepted and used due to the lack of any other available records. In William’s case, his date of birth is also accepted, while for Elizabeth, her birthday of April 29 is correctly noted, though the birth year of 1844 must be incorrect. The photographed gray and white granite marker provided by Find a Grave.com is difficult to read, but gives the following documentation.

“William M. Sauls

BIRTH 13 Jun 1831, Tennessee, USA

DEATH 13 Nov 1900 (aged 69), Texas, USA

BURIAL Jonesboro Cemetery, Hamilton County, Texas, USA

MEMORIAL ID 88501963”

“Elizabeth C. Bunting Sauls

BIRTH 29 Apr 1844, North Carolina, USA

DEATH 20 Dec 1916 (aged 72), Texas, USA

BURIAL Jonesboro Cemetery, Hamilton County, Texas, USA

MEMORIAL ID88503813”

(A suggested edit was sent to Find a Grave, and Elizabeth’s birth information has since been changed.)

For Elizabeth, it was necessary to examine the births of her siblings to determine how her birth year might fit among them, as shown in the chart below. Census records never listed Elizabeth or her elder sister, Mary, in a named accounting of family members since they were not part of the family from 1850 onward, when the census began naming family members. Mary and Elizabeth do appear to be counted in the 1840 Census of their father’s household within their respective age categories. In 1840, Samuel A. Bunting had a son who was one year old and three daughters aged three, five, and seven, and these children are counted in their age categories. By examining the chart below and considering the common two-year interval between births and the approximate gestation period of nine months, along with the 1900 Census birth information, it was concluded that Elizabeth must have been born in 1835 and was fourteen years old when she married William on October 18, 1849, in Hardeman County, Tennessee.

| Sibling Name | Birth Date |

| Mary Bunting | 3 Dec 1833 |

| Elizabeth Bunting | 29 Apr ? |

| Julia Bunting | 20 Apr 1837 |

| David Bunting | 1839 |

| Caroline Bunting | 2 Jan 1841 |

| James Owen Bunting | 14 Jun 1842 |

| Virginia B. Bunting | 16 Jun 1844 |

| Samuella Bunting | Abt. 1846 |

Not to belabor this youthful marriage any further, but how does it compare to other marriages in this family? The data below presents comparable statistics, yet Elizabeth remains the youngest bride.

William’s father and mother were 30 and 15 years old, respectively, when they married.

His siblings:

Joseph D. Sauls was 23 when he married first to E. A. “Diza” Jones, who was 19 years old.

Elizabeth Sauls was 17 years old when she married L. B. Futrell, who was 34 years old.

Amanda Sauls was 16 years old when she married John C. Russell, who was 24 years old.

David C. Sauls was 22 years old when he married E. A. Russell, who was 25 years old.

Burwell J. Sauls was 51 years old when he married M. I. Williams, who was 33 years old and

was her 2nd marriage, and very well could have been Burwell’s 2nd marriage too.

Elizabeth’s father and mother were 29 and 18 years old, respectively, when they married.

Her siblings:

Julia A. Bunting was 15 years old when she married E. O. Humphrey, who was 22 years old.

Caroline O. Bunting was 17 when she married A. N. Prewitt, who was 29 years old.

James O. Bunting was 24 when he married Sarah E. Mathis, who was 17 years old.

Virginia B. Bunting was 15 when she married William E. Robinson, who was 23 years old.

Samuella A. Bunting was 19 when she married Robert M. Wright, who was 31 years old.

Now that Elizabeth’s age is known, why was it necessary for William and Elizabeth to move forward with their adult lives at such young ages as a married couple? Wasn’t William, the eldest son, working alongside his father on the Sauls family property? The 1850 Census tells us otherwise. Burwell Sauls and family were enumerated on October 22, 1850, as dwelling and family number 814, and several pages later, William and Elizabeth Sauls were recorded on November 14, 1850, as dwelling and family number 1340, situated between the families of Daniel Gray and Hugh Gray. It was also noted that William and Elizabeth had married within that year, clearly as an independent family.

This analysis of marriage ages is excessive, and most family researchers simply report the facts without delving into the reasons or causes of events. However, let’s finally address the real catalyst that brings this young southern family into existence, which, sadly, is rooted in the subjugation of human lives.

Elizabeth’s parents, Samuel A. and Elizabeth A. (Moore) Bunting, began their lives in North Carolina, where they married. After having three children, including Elizabeth, the family moved to Hardeman County, Tennessee, around 1840, where five more children were born. Samuel died unexpectedly on April 18, 1846, just two days after writing his will on April 16, 1846. His eighth and final child, a daughter, was born that same year and named Samuella Adolphus Bunting in his honor. This family was not poor. The inventory of Samuel A. Bunting’s estate included 383 acres of land, livestock, and many enslaved individuals, which contributed significantly to the estate’s value. Samuel A. Bunting’s will named only his wife and eldest son, David, along with a few enslaved persons he thought could be dispensed with after his death to support his family. Elizabeth, despite being the eldest surviving child, is referred to only once in a court record concerning the settlement of her father’s estate.

The court record regarding Elizabeth was presented at the September Term 1850 Court and was the first submitted on behalf of the heirs of Samuel A. Bunting by John H. Raines, two months before William and Elizabeth married. The record begins with an inventory of S. A. Bunting’s estate, listing the slaves by name along with their ages, and then summarizes the remaining property. No values are assigned to the slaves or other property items. The slaves are the easiest property to divide, and when a final settlement is made for each heir, they receive a number of slaves. Though they are not married yet, William Sauls is handling “E. A. Bunting’s” settlement, and she is given a “Division of Negros.” Since a partial slave cannot be allocated, it often leads to the heir having to compensate the other heirs for the difference, and William Sauls pays $75 for this overage in settlement.

FamilySearch>Catalog>United States, Tennessee, Hardeman>Probate records>Administrators’, executors’, and guardians bonds and letters, and settlements, 1850-1920>Guardians’ settlements 1850-1871, IGN 4776571>Item 1, p. 30-31, image 47 of 375.

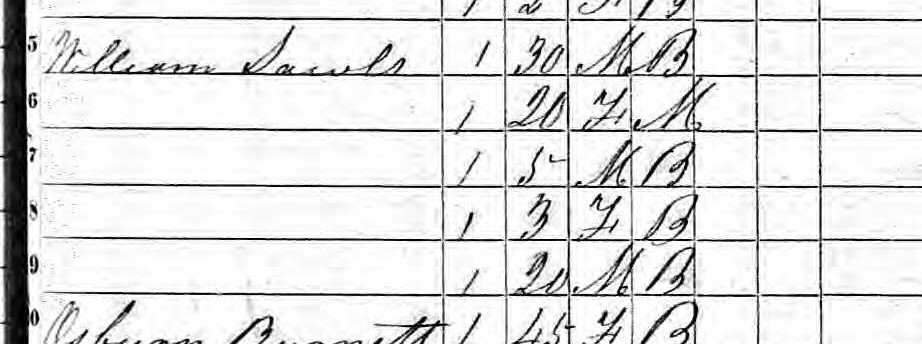

The 1850 Non-Population Census of Hardeman County, Tennessee, shown below, was recorded in November 1850, after their marriage in October, and it lists the five slaves William now owns.

1850 Census Hardeman Co., TN Non-Population Schedule

What seems strange or important is that William is controlling Elizabeth’s interests before they are married, indicating they are considered a couple and are already making future plans. Plans that perhaps accelerated with the death of Elizabeth’s father, providing them the means to make those plans a reality. Of course, this is pure speculation, but Elizabeth was fourteen (and a half) when they married! But then again, who knows? It may have been a headstrong Elizabeth directing this narrative, knowing exactly what she wanted in life and William as a means to help her achieve it, not to mention the enslaved workforce.

Coming soon – Part 3, “The Stickney / Sauls Family – William and Elizabeth Gone to Texas through Arkansas and the Civil War,” is coming soon.