Election day caused me to look back at Texas poll tax receipts I have in my family archives. To vote in Texas one had to pay a poll tax of $1.50 to $1.75. Poll taxes were first implemented in the state in 1902 and continued until 1966 when the Supreme Court ruled them unconstitutional. These receipts belonged to Bertha Mae (Stickney) Witcher Buchanan and her then husband James Edward Witcher and were kept with other tax receipts, land interest payments and registered Hereford cattle certificates in a small black metal box. On election day I was prompted to get the receipts out and explore the suffrage activities in the state of Texas to try and get a feel for what was going on in the state leading up to the 1920 national ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment giving “Mae” and all women the right to vote. Well in some, mostly southern states, the right still depended on their ability to afford to pay a poll tax.

Surprisingly I found an interesting account about women voting in Texas before 1920 in an article in the Texas Handbook, Woman Suffrage by A. Elizabeth Taylor and revised by Jessica Brannon-Wranosky that explains how Texas women were given the right to vote in a primary election. Governor James E. Ferguson was opposed to women voting and so the women suffrage organizations in Texas were against him. Fortunately for women Ferguson was impeached in 1917 and Lt. Governor William P. Hobby who was more accepting of women voters became governor. Even though Ferguson was not supposed to hold state office again after his impeachment he entered the next Democratic primary against Hobby. The state suffrage organizations got behind Hobby in exchange for women’s right to vote in political primary elections and nominating conventions. This did not require an amendment of the state constitution. Governor Hobby called a special session in March 1918 and the primary suffrage bill was introduced and approved by both the House and Senate. Hobby won the Democratic primary and was elected Governor November 5, 1918. This was really huge because for years after the civil war and reconstruction the state was decidedly Democratic so who ever won the state Democratic primary for governor was the next governor. The election was just a formality.

This article went on to state that this primary suffrage law included the only literacy test in Texas voting history and paying a poll tax was not necessary nor was it necessary to register if you lived in a town with fewer than 10,000 people which takes me back to Mae and her poll tax receipts. At the time the primary suffrage law went into effect Mae was thirty-seven years old, single, probably still living in Midland, Texas with a cousin, Sallie Perry, and working as a bookkeeper according to the 1910 census. I have no way of knowing if she participated in this primary election that took place in July 1918, since she would not have had to register because Midland’s population was less than 2000 prior to 1920.

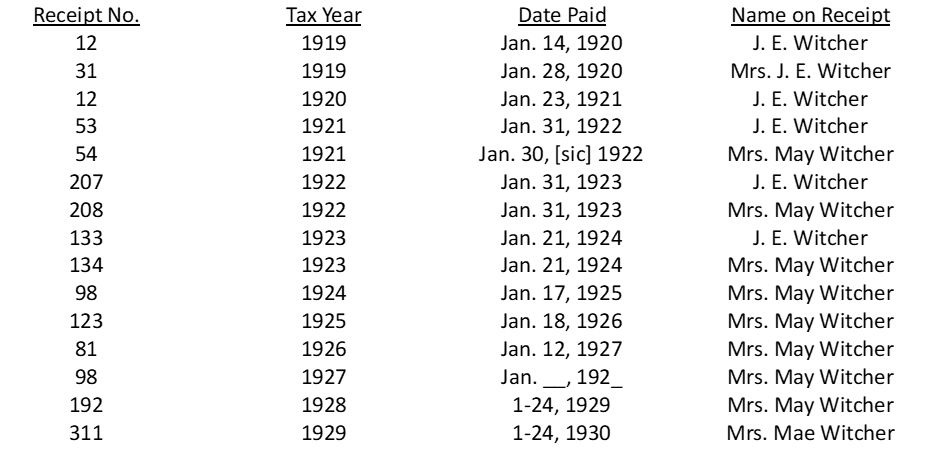

I would like to think the poll tax receipts tell me Mae was very much in favor of her right to vote that the Nineteenth Amendment gave her in August 1920. The following inventory of the collection shows there is not a poll tax receipt for Mae in 1920 for the ability to vote in 1921. I would like to imagine that the reason it is missing is because she used it to vote and therefore it is not in the collection. If that was the case then Mae’s other poll tax receipts that are in the collection were never used to access a polling location. The receipt was your ticket to get into a polling place to vote. In fact the receipts for tax year 1921, 1922 and 1923 for Mr. and Mrs. Witcher are still attached to one another the way they would have been received at the tax office and put in the black metal box for safe keeping. After 1923 there are no poll tax receipts for Mr. Witcher which I feel indicates he did use them to vote. I can’t believe he would pay Mae’s poll tax and not his own. I need to do some more research to see if did pay his poll tax during these years and if Mae paid her poll taxes in later years.

Why this collection of poll tax receipts ends in 1929 is due to the fact that James Edward Witcher died on February 20, 1931. Maybe it was Mr. Witcher who was more faithful in paying the poll taxes to have control over one more vote. My excitement of Mae’s voting right has somewhat waned after considering why the poll tax receipts were found in the black box. I personally keep my voter’s registration or ticket to vote in my purse with me at all times. Mae died November 15, 1957 so I did not know her, but due to other articles in my possession such as Bibles, prayer books, and a speech about prayer, I know she was very religious. Perhaps she was content with her husband in control of her ticket.

Genealogically poll tax receipts can give valuable information especially if all the blanks are filled in with answers. Although limited, the data in the above example confirms Mae’s age and she had been living in Ector County for only one year and no longer working since her occupation is stated as housekeeper. The ability to vote depended on the length of time you lived in the state and county so it is nice that this information is given. Clearly the race question is informative but sad this was the main reason poll taxes existed. Changes were made to the poll tax form at various times. Beginning in 1922 the sex of the individual began was noted on the receipt as well as precinct number. An important change for family historians is that birthplace was added to the 1929 receipt. This family historian will attempt to find more poll tax information on Bertha Mae and hopefully will have an update in the future. For more information on the women in Texas getting the vote, check out https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/ entries/woman-suffrage.

Pingback: B. M. (Stickney) Witcher Buchanan Part 2, J. E. Witcher’s Black Box | Forwardly Looking Back